“It all started with some music and some pills”; the story of a recovering Solon Comet

“You are who you are,” Spitaleri said. “Be proud of yourself. You’re beautiful. If someone else is going to judge you for that, [expletive] them. Tell them to hit the road, because you don’t need them in your life. They’re just holding you back.”

“I’m Nick Spitaleri, and I absolutely hate myself.”

With those eight words, a Solon High School graduate introduced himself to an auditorium filled with over 400 SHS students, most of whom he’d gone to school with just two years prior. He had but one goal in his mind: to tell his story so that others wouldn’t have the same pain that he did.

19-year-old Nick Spitaleri grew up in Lyndhurst, Ohio. He attended grade school at St. Francis of Assisi, a private Catholic school in Gates Mills, where he was constantly bullied by his peers.

“Growing up, I put on a great face,” he said. “You’d see me smiling. You’d see me happy. The truth is, I wanted to [expletive] kill everybody.”

He was just six years old when he first began to fantasize about killing himself.

“Sometimes as parents, when a child doesn’t talk to you, you don’t know how sometimes [they’re] hurting inside,” Marilyn Spitaleri, Nick’s mother, said.

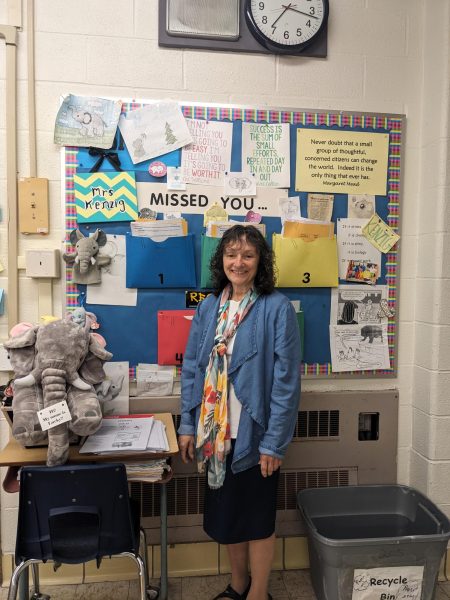

Spitaleri’s 45-minute speech to the senior class was the first time he’d spoken about his experiences in a public setting.

As the harassment at school continued, Nick was finally able to find an outlet for his overwhelming anger towards both his classmates and himself: football.

While he originally disliked the game, his dad’s encouragement and love of the sport eventually changed his opinion of it; after all, he was now able to “legally hit people.” He joined St. Francis’ team, and played there until his 7th grade year. Then, after the season ended, his family moved to south Solon. He finished out the year at St. Rita’s, where he joined the football team the next year.

Although it seemed at first that his life was improving at first, his suicidal thoughts continued to manifest, and at age 14 he almost attempted to take his life using a belt and the pull-up bar in his closet.

“It just wasn’t right, those thoughts of suicide, that anger that just makes my whole body shake,” Nick said. “I remember choking myself, just fantasizing about killing myself. I didn’t think anything was wrong with that; I thought it was just normal.”

He had four more near-attempts in the years that followed.

“He was living in a very dark place… and as his dad I kind of feel I probably should have known some of this,” Nick’s father, Carl Spitaleri, said. “And I did, but sometimes you don’t know to what extent it is.”

It was at this time that Nick first met Jim McQuaide, Head Football Coach at SHS, while he was practicing with St. Rita’s. McQuaide was observing the school’s practice, and he immediately noticed Nick’s talent. The two hit it off, and the next year, Nick persuaded his parents to let him transfer to the Solon School District for his freshman year instead of another private Catholic school in the fall of 2010.

The sheer size of the student body was thoroughly shocking, but he soon adjusted, even making Merit Roll one semester. He also continued to play football, joining the freshman team as a tight end and even moving up to the varsity level for the playoffs that same year.

But the life that he’d started to make for himself at SHS began to fall apart the summer after his freshman year when he first experimented with alcohol.

“It was like all my problems were solved,” he said. “Thoughts of killing myself, thoughts of being fat, thoughts of being … just a lonely person in a room full of hundreds– it all went away when I took that first drink.”

Even with the introduction of alcohol, Nick continued to train for football season the next fall, where he hoped to play on the varsity team as a sophomore. He ended up making the team– but just a few weeks later, he tore his ACL for the first time.

“I didn’t know how to react,” Nick said. “All my dreams got crushed. I knew I was never going to be the same. I was teetering on the edge, and football was the only thing holding me up.”

That was when prescription pain medication entered his life.

When doctors prescribed him painkillers for his knee, rather than taking the medication as prescribed, Nick would crush up the pills and snort them to get high.

“Just the euphoric rush it gave me was unbelievable,” he said. “I loved it.”

But while his problems may have temporarily gone away while he was intoxicated, they came back tenfold when he sobered up.

Nick entered rehabilitation for his knee before his junior year, but five days into summer training camp, he tore his ACL again.

“In the back of my mind I [was] relieved because I [could] get high all the time,” he recalled. “Ain’t that some [expletive]. I literally [felt] relieved that I got hurt, that I’m not playing the sport I’ve loved since I was a little kid, because I want[ed] to get high.”

His addiction continued to progress and he spent the majority of his time drinking, smoking and getting high. He started hanging around other drug users, becoming more distant from his friends. Scamming doctors for pills became a common practice, and he’d skip out on knee appointments in favor of inebriation.

“As the injuries progressed, he definitely changed,” McQuaide said. “I had always heard rumors about what was going on, but I had never delved into it deeply.”

Spitaleri and McQauide maintain a strong relationship even today.

By the time Nick entered his senior year, he was unable to come to school without getting high first.

“I was in such misery, I was in such pain, and I needed to get high so bad[ly],” said Nick, whose sobriety, although limited, plagued him with thoughts of suicide.

His pain was so overwhelming and his craving to get high was so immense that, in an attempt to avoid having to play football at the beginning of his senior year, Nick repeatedly bashed his knee with a ping pong paddle for two hours to create bone bruises.

When he returned, Nick tore his ACL again. In Nick’s mind, this was great news, because it meant that he would be prescribed more painkillers.

At one particularly low moment, he found himself blackout drunk in his girlfriend’s bathtub, puking his guts out in nothing but his underwear. When she went through his phone, she found conversations not only with drug dealers but also other girls he’d been seeing on the side, and immediately broke up with him.

“These drugs and alcohol, they’d taken everything from me already,” he said. “I wasn’t a real person.”

Soon, it became time to begin college applications. Nick only applied to two schools: Ohio University (OU) and Kent State University (KSU). With a 2.5 GPA, he knew his options were limited; and besides, he’d heard those schools were where the drugs were.

In the fall of 2014, Nick began his freshman year at KSU. From there, his addiction skyrocketed.

Just like the year before, he couldn’t attend class sober, and spent the majority of every day getting high and drunk. He’d steal money from other students in his dorm to pay for drugs, lying and cheating his way through classes.

“If I wasn’t high, I was seriously debating hanging myself every single day,” Nick said.

He didn’t even make it a semester before his college career ended after swearing at a police officer while intoxicated.

“I always thought I had bad luck,” he said. “I always thought that the world hates me, God hates me, my friends hate me, everything hates me. But really I just hated myself. I couldn’t see all the blessings that were around me.”

Now out of KSU and on his own, Nick started surrounding himself with other “junkies,” sleeping on people’s couches and doing whatever it took to stay high. He eventually found himself snorting heroin in a trailer park with crackheads and driving through inner-city Cleveland with gangsters just to get a fix. In the course of a little over a year, he lost over 90 pounds.

“I didn’t know that I was supposed to love myself,” he said.

Then, just over a year ago, Nick had what he considered to be a spiritual awakening while sitting at the table alone with his dad and his dad’s girlfriend. He recalled having an out-of-body experience in which he realized that he needed help and admitted that he should enter rehabilitation for his addiction.

He began a 12-step recovery program that involved finding a greater power and taking an in-depth moral inventory.

“It was a whole new outlook,” Nick explained. “It sucked because I had a clear mind and I saw all the damage I’d done, all the people I’d harmed. A lot of things started crashing down on me. It’s scary [expletive], but I had to go through it to find myself.”

Nick is now almost 13 months sober.

In order to correct for the pain he’s caused, he’s currently on a mission to make amends to those he’s hurt by looking them in the eyes and coming clean with the truth; and for Nick, the list of people he’s hurt is a long one.

One of his best friends recently died of a heroin overdose, a friend whose addiction he feels he helped to progress.

“I had to look her mother in the eyes at the funeral and say ‘I’m sorry, and I’ll pray for your family.’ This is where it leads us, these drugs, this way of life, that way of thinking: jails, institutions and death.”

The reality of his situation and its consequences had never been so clear.

“I can’t say I’m sorry anymore,” he said. “I ran out of them. ‘Sorry’ is just a word. You really show you’re sorry with your actions.”

A few weeks ago, Nick returned to Solon to talk with someone high up on his list of people he’s wronged: Coach McQuaide.

“I was very sad,” McQuaide said. “You always think about what [you] could’ve done to help along the way.”

McQuaide told Nick that all he needed to do to make amends with him was to stay sober, but Nick felt that it wasn’t enough. He had to atone for the damage he’d done by lying and acting as a negative influence toward the rest of the student body, particularly toward the football team.

As per this request, McQuaide worked with SHS principal Erin Short, as well as other members of the administration, to set up a time for Nick to share his story with the current student body.

“I guarantee somebody in this [school] is going through the same thing that he’s gone through, or will go through what he’s gone through,” Short said. “And there’s really nothing more serious than a matter of life and death.”

On April 21, juniors and seniors gathered in the auditorium for one period each to listen to Nick speak. Not only was it important to Nick that these kids in particular heard his story because they were much closer to starting college, but also because the majority of these upperclassmen attended high school alongside him.

“I think what he did was very brave,” Carl Spitaleri said. “It’s very hard, he went to school with a lot of these kids and he admitted a lot of things that probably were not really easy for him to admit. But his path in life, I believe, is going to be helping people, and this is just the beginning of the journey for him.”

Nick admitted that this degree of honesty was difficult, although it was not as scary as he’d imagined it to be. He didn’t prepare his speech; he just prayed and talked.

“It was unbelievable feeling that energy,” he said. “It was very calm, very still, and it was honestly calming. I’m just happy people listened.”

For many of these listeners, Nick’s story and brutal honesty had a profound impact.

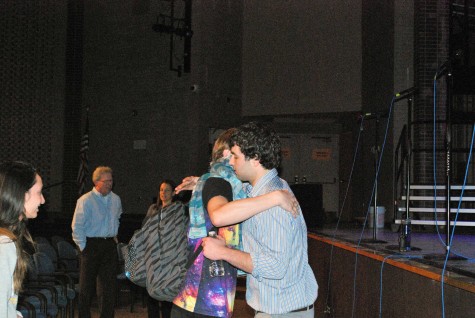

Spitaleri embraced Webster after an emotional conversation.

“It’s eye-opening,” SHS junior CJ Webster said. “You hear about [addiction] all around the world, but you don’t really see it from that standpoint. I appreciate everything that he’s doing, coming out here and speaking because it’s really hard, I’m sure. I think that he helps [students] because they’re more willing to speak about their problems.”

Nick’s story, while hard to hear, was extremely powerful, particularly for some students who personally knew him during his time at SHS.

“I saw [Nick] when I was a sophomore and I thought man, I really want to be like that guy,” said current senior Hunter Jenkins, a football player who, like Nick, has suffered from multiple ACL injuries. “Anybody with the guts to come back to the place that they started and admit their problems and help make amends and try to help people better themselves so they don’t have to go through your shoes, I heavily respect.”

Marilyn and Carl Spitaleri, who attended both sessions of the assembly, stressed that if Nick impacted and affected just one student, then he’d “done his job.” Short and McQuaide also share this same sentiment.

“Everyone has issues, things we have to deal with,” McQuaide explained. “Like Nick said, we stick together and we help each other out. You hear all the time about ‘We are SC’. This is a perfect example of ‘We are SC’. Once you are a Comet, you are always a Comet.”

Nick hopes that his story will provide a cautionary tale for many. He doesn’t want anyone to go through what he did, he said, but this is just the reality of it. For every person like him speaking out against drugs, there are even more outside influences encouraging their usage, particularly in music such as rap. Especially for Nick, “it all started with some music and some pills,” which changed his life forever.

“That’s not the real world,” Nick said. “That’s going to lead to pain and misery, I see it every single day. If you’re not golden inside, all the gold in the world on the outside ain’t gonna change that, I promise you that. We’re all together in this. The only way to get out of ourselves is others, the only way we can save ourselves is by helping others.”

After the assembly ended, McQuaide helped distribute preventative information and resources, knowing as Nick does that there are still many people out there struggling.

“Nothing is ever hopeless unless we make it hopeless,” McQuaide said. “No matter where you’re at– because we all have those moments– there’s somebody here that can try to get you out of that hopelessness, to help you out.”

If you or someone you know misuses or is dependent on drugs or alcohol, there is help available. Students can talk to a parent/guardian, school counselor, teacher, coach, spiritual adviser or any other responsible adult. For additional information and resources, you can contact New Directions, Catholic Charities, Recovery Resources or SAMHSA’s National Helpline.

![“You are who you are," Spitaleri said. "Be proud of yourself. You’re beautiful. If someone else is going to judge you for that, [expletive] them. Tell them to hit the road, because you don’t need them in your life. They’re just holding you back.”](https://theSHSCourier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/ChillinWeb-900x602.jpg)