Are people free to hate?

Picture courtesy of cleveland.com.

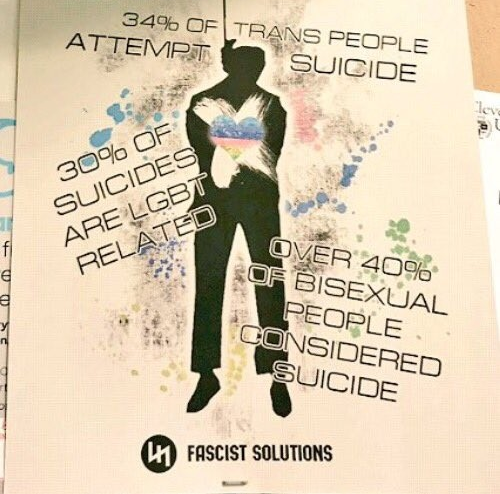

This anti-LGBTQ+ flyer was found on a CSU billboard.

December 1, 2017

On October 12, an anti-LGBTQ+ flyer was posted on a billboard at Cleveland State University (CSU). The flyer displayed an image of a person being hung by a noose under the words “follow your fellow fa*****.” Surrounding the image were statistical claims about LGBTQ+ suicides, insinuating that people of the LGBTQ+ community should kill themselves. The flyer was immediately taken down, but the incident initiated outrage across campus.

Representatives from CSU issued a statement condemning the flyers.

“Hate has no place in our community. It never will. We unequivocally condemn the abhorrent message on these flyers,” the statement read.

The person who posted the flyer did not go through proper channels to display it. To display a flyer, students must get an approval stamp by CSU Conference Services. It is unclear whether or not the university would have allowed the flyer to remain up if the person had followed protocol.

According to cleveland.com, CSU Director of Communications and Media Relations William Dube said that the flyer would have remained on the billboard if the person went through the correct process of posting flyers.

However, when The Courier reached out for further clarification, Dube declined to speculate on hypotheticals.

The CSU anti-LGBTQ+ flyer is only one of the most recent incidents in the free speech versus hate speech issue. For example, in August of 2017 white supremacists held an alt-right rally in Charlottesville, leading to debates about the freedom to express hatred and organize protests. Due to the far-reaching implications of First Amendment issues, Solon High School Government teacher Mary Clare Lane said that she feels it is important for students to learn about free speech and hate speech conflicts and the CSU incident.

“It’s CSU; it’s in our backyard. This kind of thing can and does happen everywhere,” Lane said.

Lane also believes that the free versus hate speech issue also impacts anyone who wants to protest.

“We should all know how protected we are in different forms of speech and different forms of actions so that when someone wants to take action…[they] know what type of protections [they] have,” said Lane.

Protesters cannot infringe upon someone else’s rights while trying to prove their point. Issues involving conflicting fundamental rights can be especially sensitive.

“If that student fascist group had followed CSU protocol [to post the flyer], and that flyer had gone up, as a student, I probably would have walked by and ripped it down, but then would I have been facing repercussions then denying someone else their right to free speech?” Lane said.

Hate speech can put schools in a precarious situation. Some people equate censorship of hate speech with an infringement upon First Amendment liberties. This begs the question, how can schools protect students from hate while simultaneously protecting free speech?

School psychologist and adviser of the Gay Straight Alliance Club (GSA) Valerie Smith stated that she believes free speech is vital, but it is also important to discourage hate speech.

“There’s a balance,” Smith said. “You don’t want to stop people from expressing their beliefs and their rights, but you also just have to make sure it’s not creating [a] hostile or negative climate.”

Lane expressed a similar philosophy. She said that hate speech is repulsive, but it is difficult to suppress it without limiting free speech.

“I’m never going to be one to advocate for censorship, but on the same side of that coin, I find it abhorrent that we can tolerate extreme levels of hate speech,” Lane said. “In public when you start censoring the things that people say, it becomes very difficult to draw a line. Where do you stop?”

Finding the balance between censoring hate speech and protecting free speech is tricky, and most people do not have a clear cut opinion. However, many people agree that hateful events such as the anti-LGBTQ+ flyer at CSU have ramifications that reverberate far beyond the boundaries of campus.

Smith said that she believes that when hateful events occur, students at SHS need to reflect on themselves and modes of social change. She expressed that one of her primary concerns is that students will internalize their concerns about threats and hate speech.

“Students do need to focus on what their beliefs are and what they can do to change [hateful ways of thinking],” Smith said.

On the administration side, Smith said that school principals and advisors need to determine the reason a student expressed hate.

“Number one, [schools] have to, obviously, talk with the person [who expressed hate] and find out, what is the intent,” said Smith.

The First Amendment dictates that laws cannot be made to abridge free speech. However, several court cases established limits to what people can say. For example, the 1942 Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire case determined that “fighting words,” language that promotes the disruption of peace, also fall under the domain of unprotected speech.

However, limits to hate speech are few and far between. In the 1969 Brandenburg vs. Ohio case, the Supreme Court declared an Ohio criminal syndicalism law, a law that prohibits advocating for illegal acts, to be unconstitutional because it abridged the free speech of Clarence Brandenburg, a leader of the KKK.

“People have the right to say horrible, terrible things,” Lane said.

When hate speech or symbolic hate speech is expressed on school property, however, schools have some legal grounds for censorship. In the 1969 Tinker vs. Des Moines case, the Supreme Court ruled that schools can limit student expression if it constitutes a disruption to the school day. However, there is still a legal gray area for what constitutes harassment and what is disturbing to the learning environment.

Lane stated that she believes that the vile intent of the flyer disturbed students and disrupted class.

“Within a school setting, any speech that advocates for hate is naturally, I think, going to disrupt the learning environment,” Lane said.

Junior Charlie Simecek, co-president of GSA, said that she believes teachers should take an active role in condemning acts of hatred. She said she feels teachers can have a positive impact by doing something as simple as telling students that they do not condone a hateful event. Simecek also wants students to show support for LGBTQ+ issues.

“[Issues like these] affect a lot more people than [students] think [they do],” Simecek said.

Many people believe that there has been a recent rise in hateful rhetoric, but Lane believes that future generations will play a role in spreading tolerance.

Lane said that there is no room for tolerance of hate in any form.

“I think younger generations are already better at working together and cooperating together…than a lot of the older generations,” Lane said.

Wenzhao Qiu • Nov 30, 2018 at 6:21 pm

Were there any other posters? It doesn’t seem like the poster shown was insinuating that LGBT people should kill themselves. Even though it was from a fascist organization, it looked more like they were just listing off facts for why they thought being LGBT is harmful. So this seems more a product of ignorance than actual malice to me.

For me, hate speech is a threat or anything else that blatantly incites violence against others. The poster doesn’t really fit that criteria from my perspective.